"When Martin Luther King was writing his letter from the Birmingham Jail, when JFK and his brother were gunned down, when body counts and flag-draped coffins were part of our TV diet, when Jimi and Janis, free love, Kent State, and civil rights marches to Selma, Alabama were our daily bread, there existed a parallel universe mostly untouched by these events. There existed the golden age of baseball."

- Ron Shelton, from his introduction to Neil Leifer's Ballet in the Dirt: The Golden Age of Baseball

Above: Rawlings ad, 1964.

Despite never winning a Cy Young Award, Juan Marichal was one of the premier pitchers of his era, posting 243 wins and a 2.89 ERA for his career. "The Dominican Dandy," who utilized a high leg kick in his windup, won 20 or more games six times for the Giants.

1966 Topps baseball card

It would take the expansion Los Angeles (later California) Angels nearly two decades to reach their first postseason. One of the few bright spots in the early years of the franchise was the phenomenal season Dean Chance put together in 1964 (a league-leading 20 wins, 1.65 ERA, 15 complete games, and 11 shutouts) to win the joint A.L.-N.L. Cy Young Award.

1965 Topps baseball card

On June 21, 1964, Jim Bunning pitched a perfect game against the New York Mets. It was the first perfect game in the National League in eighty-four years.

Signed photo

Metropolitan Stadium, Bloomington, Minnesota, home of the Minnesota Twins (formerly the original Washington Nationals/Senators).

Postcard

Above and below: the 1966 Twins yearbook.

The Twins took the A.L. Pennant in '65, and staked themselves to a quick two games to none advantage in the Series. But they were unable to close the deal versus the Dodgers and their unbeatable ace Sandy Koufax, who had famously not pitched game one, choosing instead to observe Yom Kippur.

Twins slugger Harmon Killebrew led the A.L. in home runs six times, and was voted the league's MVP in 1969. In his Hall of Fame career the amiable "Killer" amassed 573 home runs, placing him fifth on the all-time list upon his retirement following the 1975 season.

1965 Topps baseball card

Tony Oliva, one of the best on an impressive list of Major League ballplayers hailing from Cuba, earned A.L. Rookie of the Year honors in 1964, leading the junior circuit in runs scored (109), hits (217), doubles (43), batting average (.323), and total bases (374). He went on to win two more batting titles, in 1965 and '71, as well as leading the league in hits four more times and doubles three more times, before knee injuries brought his career to a premature end in 1976.

Above: 1969 Topps baseball card

Below: Signed photo

Above and below: 1965 Topps baseball cards

After having been tenants of the Dodgers for four of their first five years of existence, the Los Angeles/California Angels finally had their own brand new stadium in 1966.

Postcard

Sandy Koufax, who would win his second of three Cy Young Awards in 1965, famously chose not to start Game 1 of that year's World Series because it fell on Yom Kippur. He and his Game 1 replacement, Don Drysdale, would lose the first two games to the Minnesota Twins, setting up a dramatic Dodger comeback that was spearheaded by shutout pitching from Sandy in his remaining two starts -- including the finale, in which he struck out 10 and allowed only 3 hits.

Above and below: 1966 Dodgers yearbook.

Walter Alston (pictured on the cover above) managed the Dodgers to seven Pennants -- including their last in Brooklyn and their first in LA -- and four World Championships in his 23 years at the helm.

Future Hall of Famer Sandy Koufax was the MVP of the 1963 and '65 World Series, the N.L. MVP in '63, and the winner of the combined A.L-N.L. Cy Young Award in 1963, '65 and '66. He retired at the age of 30 after the 1966 season.

Sandy Koufax's 1963 Topps baseball card.

Above and below: 1966 Baltimore Orioles yearbook.

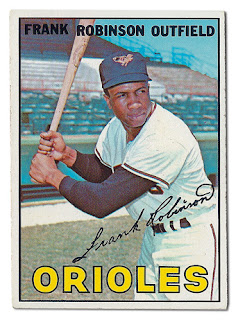

Powered by Triple Crown winner and MVP Frank Robinson, a future Hall of Famer, the O's stunned the reigning World Champion Dodgers in four straight in the '66 Fall Classic. Their third baseman was another Hall of Famer, 1964 A.L. MVP Brooks Robinson, who would later dazzle with his glove in the 1970 World Series vs. the Cincinnati Reds.

Frank Robinson's 1967 Topps baseball card.

World Champions Brooks and Frank on the 10-10-66 cover of Sports Illustrated.

Above and below: 1967 Dexter Press photo prints

Above and below: Postcards of Baltimore's Memorial Stadium, home to the Orioles and the NFL Colts.

Jim Bunning became only the second pitcher in Major League history to strike out 1,000 batters in each league. The first was Cy Young.

Above: 1963 and 1965 Topps baseball cards

Below: 1967 Dexter Press photo print

Above and below: 1967 Topps baseball cards

Combative, obstreperous, controversial Leo Durocher managed the erstwhile butt of baseball jokes, the Brooklyn Dodgers, to their first Pennant in two decades in 1941. But after a falling out with team president and general manager Branch Rickey midway through the 1948 campaign, "The Mahatma" sent "The Lip" packing to Brooklyn's hated cross-town rivals, the Giants, stunning the baseball world. Leo proceeded to lead them to their first Pennant in fourteen years in 1951 (see "Shot Heard 'Round the World" in Part 1), and their first World Championship in twenty-one years (and their last for fifty-six) in 1954.

By the time he arrived in Chicago in 1966, the Cubs had been dwelling in or near the cellar since 1947, and owner Philip K. Wrigley had recently resorted to a "college of coaches," having, temporarily at least, given up altogether on the concept of a team manager. After leading the Cubbies to another last place finish in his first year at the helm, Durocher brought a modicum of respectability to the North Siders with a handful of 2nd and 3rd place finishes -- the most (in)famous of which came in 1969, when, after a summer of sitting comfortably atop the newly configured N.L. East they faded dramatically down the stretch, relinquishing the division title to the miraculously surging Mets.

By the time he arrived in Chicago in 1966, the Cubs had been dwelling in or near the cellar since 1947, and owner Philip K. Wrigley had recently resorted to a "college of coaches," having, temporarily at least, given up altogether on the concept of a team manager. After leading the Cubbies to another last place finish in his first year at the helm, Durocher brought a modicum of respectability to the North Siders with a handful of 2nd and 3rd place finishes -- the most (in)famous of which came in 1969, when, after a summer of sitting comfortably atop the newly configured N.L. East they faded dramatically down the stretch, relinquishing the division title to the miraculously surging Mets.

Scrappy Eddie "The Brat" Stanky, Durocher's favorite player when he was managing him with the Dodgers, and later the Giants, took over a pitching-rich, hitting-poor White Sox team that had long enjoyed considerably more success than their North Side counterparts, even winning an A.L. Pennant in 1959. They had consistently outdrawn the Cubs as well, but that began to change in the mid-'60s as urban decay made its way across America's inner cities to Chicago's South Side, bringing about reluctance among many suburban fans to make the trek to 35th and Shields. The ChiSox were in contention for the Pennant with three other teams during the 1967 season, falling short only in the final week. Nevertheless, thanks largely to a poor start, Stanky was fired 79 games into the '68 season.

Sports Illustrated, February 28, 1966

Perennial All-Star third baseman Ron Santo's fielding and hitting provided a harmonious chord in the 1960s version of the traditional Chicago blues.

1967 Dexter Press photo print

One of the predominant hitters in the National League throughout the 1960s (he won four batting titles), Pirates right fielder Roberto Clemente also possessed a legendary throwing arm. In 1973 he became the first Latin player to be enshrined in the Hall of Fame.

Above: Sports Illustrated, July 3, 1967

Below: 1967 Dexter Press photo print

Sports Illustrated, February 28, 1966

Perennial All-Star third baseman Ron Santo's fielding and hitting provided a harmonious chord in the 1960s version of the traditional Chicago blues.

1967 Dexter Press photo print

One of the predominant hitters in the National League throughout the 1960s (he won four batting titles), Pirates right fielder Roberto Clemente also possessed a legendary throwing arm. In 1973 he became the first Latin player to be enshrined in the Hall of Fame.

Above: Sports Illustrated, July 3, 1967

Below: 1967 Dexter Press photo print

The St. Louis Cardinals made it to three World Series in the 1960s, winning two of them.

The Cardinals' Opening Day lineup, April 1967.

Left to right: SS Dal Maxvill, 2B Julian Javier, 3B Mike Shannon, 1B Orlando Cepeda, CF Curt Flood, RF Roger Maris, C Tim McCarver, LF Lou Brock, P Bob Gibson. In six months they would be World Champions. Photographer: Paul Ockrassa

St. Louis Globe-Democrat wire photo, dated April 9, 1967

The Cardinals' perennial All-Star/Gold Glove center fielder Curt Flood and Boston's Triple Crown-winning MVP Carl Yastrzemski, 1967 World Series foes.

All Star Sports magazine, August 1968

Four stars of the 1967 World Series, on the cover of Sports Review's Baseball, 1968.

Lou Brock stole a record seven bases and led all Series batters with a .414 average; Jim Lonborg tossed a 1-hitter in Game 2 and dominated the Cardinals up until Game 7, which he pitched and lost on only two days' rest; Yastrzemski batted .400 with three home runs; Bob Gibson tied a Series record by pitching three complete game victories -- the third (Game 7) on only three days' rest, incidentally -- as he silenced Boston's bats and wagging tongues. (Some bad blood between the opposing teams flowed throughout the series, exacerbated by Red Sox manager Dick Williams, who, when asked by reporters what his Game 7 lineup would be, replied, "Lonborg and Champaign" . . . providing some potent bulletin board material for the Cardinals' clubhouse.)

Hounded by injuries and hostile New York sportswriters ever since breaking Ruth's sacrosanct single season HR record, Roger Maris found himself back in the Heartland from whence he came in 1967, finishing his career in happiness with the Cardinals. Hitting at a .385 clip, he led all batters in the '67 Series with seven RBI.

Baseball Digest, May 1967

1967 World Series ticket stub.

Above and following: the 1968 Cardinals yearbook.

The Cards ran away with the National League Pennant in '67, thanks to Orlando "Cha Cha" Cepeda's MVP season and despite the temporary loss of ace Bob Gibson. Another major contributor was leadoff hitter Lou Brock, the N.L.'s leading base stealer and run scorer, and the spark that ignited both the St. Louis offense and Busch Stadium crowds. All three, plus a young left-hander named Steve Carlton, would end up in the Hall of Fame.

1967 National League Most Valuable Player Orlando Cepeda.

Street and Smith's Baseball Yearbook, 1968

Orlando Cepeda signed photo.

Sports Stars of 1968: Baseball, spring 1968

Above: Lou Brock signed photo

Below: Converse ad, 1969-'71

Steve Carlton's favorite catcher, Tim McCarver led all hitters in the 1964 World Series with a .478 average. After his retirement from baseball, McCarver became a familiar network baseball color commentator and analyst, and in 2012 was the recipient of the Ford C. Frick Award.

Sports Illustrated, September 4, 1967

Brock wreaked havoc on Boston batteries throughout the '67 Series, hitting a series high .414, scoring a series high eight runs, and stealing a World Series record seven bases.

Sports Illustrated, October 16, 1967

1967 Cardinals team photo.

From September 3, 1965 to June 2, 1967, Cardinals center fielder Curt Flood set a National League record for consecutive games without committing an error (226)* and a Major League record for consecutive errorless chances in the outfield (568). In addition to Sports Illustrated, no less an authority than Willie Mays cited Flood as the best center fielder in baseball in the 1960s.

Sports Illustrated, August 19, 1968

* Another Cardinal, Jon Jay, currently holds the record for N.L. center fielders, having surpassed Flood's mark in July of 2013.

The competitive and intimidating Bob Gibson missed nearly two months of the 1967 Pennant race due to a fractured right leg he sustained from a line drive off the bat of Roberto Clemente in July. Not realizing the seriousness of the injury, Gibson continued to pitch to the next few batters before his tibia broke completely and he collapsed on the mound. He would be back in time to finish the regular season and go on to earn MVP honors against Boston's "Impossible Dream" team in the World Series.

Paperback edition of From Ghetto to Glory, 1968

The Cards cruised to a repeat N.L. Pennant in '68, and were well paid for it, at least by the standards of the day. In fact, the inflation-adjusted combined salary of the starting eight, plus Gibson and manager Schoendienst, was equivalent to only about $4,135,800 in 2016 -- just over the average player salary. Nevertheless, according to writer David Halberstam in his excellent and enlightening book October 1964, team owner August Busch blamed the Cardinals' World Series loss to the Tigers in part on their fat paychecks, and he let them know it in a rambling dressing down of the team in the Cards' spring training locker room in March of 1969. Busch seems to have poorly assessed a quality group of individuals. Halberstam: "In 1968, what was essentially the same team [as the 1967 World Champions] won [the Pennant] by almost the same margin. The Cardinal players were uncommonly proud to be part of those teams, for they won not by dint of pure talent or pure power -- San Francisco was far richer in terms of pure talent. Rather, they won through intelligence, playing hard and aggressively, and because they had a sense of purpose that cut across racial lines in a way that was still extremely unusual in the world of sports." (p. 360)

Sports Illustrated, October 7, 1968

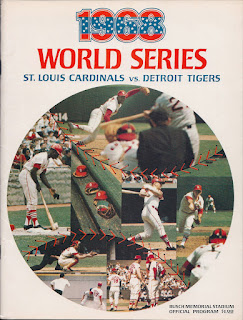

1968 World Series program, St. Louis version.

Gibson outdid himself and everyone else in 1968, putting together one of the most dominant seasons of any pitcher in history. Throwing over 300 innings and striking out 268 batters, he logged a jaw dropping earned run average of 1.12 -- allowing one or fewer runs in 24 of 34 starts. He shut out his opponents 13 times, at one point allowing only two earned runs over a ten game stretch. Compiling 22 wins, Gibson's teammates somehow managed to lose nine games when he was on the mound, six of them by one run margins. Topping off his amazing season, Gibson proceeded to strike out a record 17 Detroit Tigers in Game 1 of the World Series en route to breaking his own record of 31 K's in a Series, set three years earlier against the Yankees. He struck out 35 in the 1968 Classic. But the magic would wear off in Game 7 when, after six innings of a scoreless deadlock vs. the Tigers' Mickey Lolich, the normally flawless Curt Flood misjudged a fly ball with two outs in the 7th, allowing 2 runs to score. The Cardinals lost the game and the Series.

Above: The Sporting News, October 19, 1968

Below: 1968 MVPs Denny McLain and Gibson, Sport World, April 1969

The same pitchers on Street and Smith's 1969 Baseball Yearbook

Bob Gibson's 1968 Topps baseball card.

Above and below: St. Louis' Busch Memorial Stadium, now remembered as "Busch II," completed in 1966 and razed after the 2005 season.

Postcards

A freestanding in-store counter display, probably for 1969 Cardinals schedules. The illustrator was the legendary Bob Peak.

After toiling with the Tigers for 16 years, future Hall of Famer Al Kaline finally made it to a World Series in 1968.

Above: 1969 Topps baseball card

Below: 1967 Dexter Press photo print

In 1968, "The Year of the Pitcher," Denny McLain made history by becoming the first hurler since Dizzy Dean in 1934 to win 30 games. He won the A.L. Cy Young and MVP awards that year, en route to a World Championship. He became a big celebrity, appearing on the Ed Sullivan Show, The Smothers Brothers Comedy Hour, The Today Show, a Bob Hope special, and the Joey Bishop Show. An accomplished organist, he received a $25,000 endorsement deal with Hammond Organs, and released two albums on Capitol records. In 1969 he won 24 games and a second consecutive Cy Young award, tying with Baltimore's Mike Cuellar. He had it all. Then the wheels fell off.

Above: Sports Illustrated, September 23, 1968

Below: LP record album, 1969

Postcard of Tiger Stadium (formerly known as Navin Field and Briggs Stadium) in the 1960s.

Hall of Famer Carl Yastrzemski, who was the last MLB triple crown winner (1967) until Miguel Cabrera in 2012, had two indisputably great seasons at the plate: 1967 and 1970 (OPS 1.040 and 1.044, respectively).

1967 Dexter Press photo print

1968 Louisville Slugger bat ad

After a decade of franchise shifts, both leagues expanded in 1961-62 (countering a Branch Rickey-spearheaded threat of a third major league), and again in 1969. New teams sprang up in Anaheim, Washington, D.C. (as the original Senators/Nationals became carpetbaggers in Minneapolis-St. Paul), Houston, New York (the Mets replacing the departed Dodgers and Giants), Montreal, San Diego, Kansas City, and Seattle (which was able to field a team for only one season, the Pilots navigating their way to Milwaukee by opening day of 1970). With a combined total of eight new teams, MLB sought to level the playing field in 1969 by splitting each league into two divisions and introducing a postseason playoff system. In 1977, the A.L. would award yet another franchise to Seattle, as well as one to Toronto, the N.L. not answering until 1993 with Colorado and Miami. Both leagues would expand yet again in 1998, adding Phoenix and Tampa Bay to the mix. Along the way, the "new" Senators moved to Texas and became the Rangers, and the Expos left Montreal for D.C. to become the Nationals, that city's third different franchise.

Confused? Then I won't even bring up realignment.

1969 Topps baseball cards

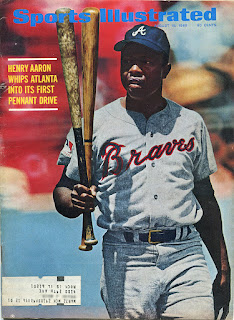

The subhead of the cover story of the August 18, 1969 Sports Illustrated reads as follows:

"For years Henry Aaron performed in comparative obscurity while compiling a record that makes him one of baseball's all-time hitters. Now, as Atlanta fights for a pennant, he finds he is famous at last."

Within a few years Hammerin' Hank's would be a household name.

Above and following: 1970 New York Mets yearbook.

Perennial doormats from their inception in 1962, the "Miracle Mets" of 1969 shocked the world with not only a Pennant but a World Championship over the powerful Baltimore Orioles juggernaut. As their former manager Casey Stengel observed, they were indeed "amazin'."

Tom Seaver won his first of three Cy Young Awards in 1969, going 25-7 with a 2.21 ERA for the World Champion Mets.

Above: 1973 Topps baseball card

Below: 1969 Topps baseball card

Yankees legend and Mets coach Yogi Berra pitches Yoo-Hoo in a 1970 magazine ad.

Following the 1969 season, the Cardinals traded Curt Flood, Tim McCarver, Joe Hoerner, and Byron Browne to the Philadelphia Phillies for Richie Allen, Cookie Rojas, and Jerry Johnson. Flood, an established veteran and star, didn't want to go, and he decided to challenge baseball's much longer-established reserve clause. In December he wrote the following in a letter to Major League Baseball Commissioner Bowie Kuhn:

"After twelve years [sic] in the Major Leagues, I do not feel I am a piece of property to be bought and sold irrespective of my wishes. I believe that any system which provides that result violates my basic rights as a citizen and is inconsistent with the laws of the United States and of several states.

"It is my desire to play baseball in 1970, and I am capable of playing. I have received a contract offer from the Philadelphia club, but I believe I have the right to consider offers from other clubs before making any decision. I, therefore, request that you make known to all Major League clubs my feelings in this matter, and advise them of my availability for the 1970 season."

Kuhn denied Flood's request, Flood sued, and the case went all the way to the Supreme Court, which ruled in favor of Kuhn and Major League Baseball. Nevertheless, Flood's stand led directly to the "10-5 rule," and ultimately to free agency.

Baseball was changing.

Above: 35mm slide of Curt Flood

Four National League sluggers in the visitors' locker room of RFK Stadium, on the occasion of the 1969 All-Star Game.

Ron Santo was enjoying his sixth of nine All-Star seasons and would drive in a personal best 123 runs that year. Willie McCovey would lead the N.L. in home runs, RBI, slugging, and on-base percentage en route to the MVP Award. Thirty-eight-year-old Willie Mays, in the twilight of an unmatched career, would still manage to hit 28 home runs the following year. Cleon Jones, whose Mets were five games out of first place in the N.L. East, their miracle finish not yet a twinkle in manager Gil Hodges' eye, was in the middle of a career year in which he would wind up with a robust .340 batting average.

1970 Adirondack bat ad

Unfortunately, for all of the historic and exciting things that happened on the field in the 1960s and '70s, it was also the era that replaced most of the grand old character-rich ballparks that had been built in the early part of the 20th century with, for the most part, sterile, unimaginative, multi-purpose stadia. These bowl-shaped mother ships would be a scourge on the landscape for the next forty-plus years, by which time tastes in architecture had come full circle, and a trend toward "retro" style parks (fashioned, to varying degrees of effectiveness and authenticity, after the classic designs and asymmetrical contours of the very ballparks that had been demolished in favor of the bowl-parks) was complete. Arguably the worst of these '60s-'70s eyesores were Philadelphia's Veterans Stadium and Cincinnati's Riverfront Stadium, which were even duller and less discernible from each other on the inside than they were on the outside.

Above: Postcard of Riverfront Stadium

Below: Postcard of Veterans Stadium

In 1962 Frank Howard, a 6'7", 250 lb. colossus of a man, set the Los Angeles Dodgers' single season home run record, which stood for twelve years. After being traded to the expansion Washington Senators, he set their single season home run record in 1969 and won two A.L. HR titles while averaging 45 from 1968-70. For some perspective, bear in mind that in 1962 the Dodgers played half their games in pitcher-friendly Dodger Stadium, and 1968 was the "Year of the Pitcher," in which nobody else in either league managed more than 36 round-trippers (Frank hit 44).

Frank Howard signed photo.

Above and below: 1971 Topps baseball cards

Twenty-two-year-old catching phenom Johnny Bench tore up the N.L. in 1970, winning the MVP with a league leading 45 homers and 148 RBI. He and his Reds turned out to be no match for the Orioles, or their slick-fielding third sacker Brooks Robinson, who put on a clinic in the World Series.

Paperback book, 1971

The 1969-71 Baltimore Orioles were a seemingly unstoppable force of nature, at least in the A.L., where they won the Eastern Division title by double-digit margins and swept their ALCS opponents three games to none in each of those years, while compiling a combined 318-164 regular season record. Manager Earl Weaver's strategy of stocking the O's with great pitching and defense, then waiting for big innings from his powerful offense, worked like a charm. It was different story when they got to the World Series, though, as the Birds managed to win only the 1970 Fall Classic.

Above and following: 1971 Orioles yearbook.

Tom Seaver (as depicted by ubiquitous illustrator Jack Davis) in a 1971 Spalding ad.

The Cubs never arrived in 1971, but Fergie Jenkins did, leading the N.L. with 24 wins and nabbing the Cy Young Award -- Seaver's superior numbers in nearly every other category notwithstanding. He would lead the A.L. in wins three years later with 25 for the Texas Rangers, en route to the Hall of Fame.

Sports Illustrated, August 30, 1971

To commemorate the 25th anniversary of Sport magazine in 1971, its editors voted on the top player in each major sport over the past 25 years. Willie Mays was their choice for baseball.

Above: Sport magazine, September 1971

Below: 1967 Dexter Press photo print

Above and following: the Pittsburgh Pirates' 1972 scorebook.

The '71 Pirates, on the shoulders of slugger Willie Stargell and his 48/125/.295 season, earned a berth in the World Series where they were led to victory over the Orioles by Roberto Clemente and his .414 Series batting average. Clemente would tragically die in a plane crash while on a mission of mercy to earthquake stricken Managua, Nicaragua in December of 1972. Both Clemente and Stargell are in the Hall of Fame.

Above: Roberto Clemente's 1971 Topps baseball card.

Above and following: 1972 Pirates yearbook.

Vida Blue became a household name in the summer of 1971, compiling a 22-4 record by mid-July. He finished the season 24-8 with 301 K's and a league-leading 1.82 ERA -- good enough to win the A.L. MVP and Cy Young awards.

N.L. MVP Joe Torre, a five-time All-Star catcher with the Braves (traded to the Cardinals in 1969 for Orlando Cepeda) moved to third base in the spring of '71 at the behest of manager Red Schoendienst. It apparently suited him, as he led the league with 230 hits, 137 RBI, 352 total bases, and a .363 batting average.

Above: Paperback book, 1972

Below: Sports Illustrated, April 10, 1972

In May of 1972 the Giants traded an aging Willie Mays to the New York Mets, thereby bringing about his return to the city where his Major League career began. He also made it back to the World Series one more time during his stint with the Metropolitans, albeit in a losing cause vs. the Oakland Athletics, in 1973.

Willie Mays signed photo.

Royals Stadium, opened in 1973, part of the Truman Sports Complex in Kansas City, Missouri.

Postcard

Above and following: the 1974 edition of the Oakland Athletics' yearbook.

Stumbling across the continent from Philadelphia to Kansas City to Oakland between 1955 and '68, the hapless A's finally found the key to success under controversial owner Charlie Finley in the early 1970s. Behind the hitting of 1973 MVP Reggie Jackson and the relief pitching of Rollie Fingers, "The Mustache Gang" would win three consecutive World Series from 1972-74 before falling victim to free agency later in the decade.

Above: Reggie Jackson's 1971 Topps baseball card.

Below: Time magazine, June 3, 1974

The A's cruised to their third consecutive championship in 1974, defeating the resurgent Dodgers (who had been absent from the postseason for seven years, which was quite a long stretch for them at the time) four games to one in the World Series.

Sports Illustrated, October 21, 1974

Above and below: 1974 Topps baseball cards

Troubled, misunderstood . . . call him what you will, the talented Richie Allen spent seven mutually unhappy years with the Philadelphia Phillies, then bounced around the National League for a couple more before moving to the hitting hungry A.L. in 1972, changing his name to Dick, and walking away with MVP honors to the tune of a .603 slugging percentage.

Steve Carlton, traded to the cellar dwelling Phils in the winter of 1972, ended up winning 27 games that year -- the rest of the staff combined managed only 32. The future Hall of Famer also won the Cy Young award, leading the league in most of the major pitching categories, including wins, strikeouts (310), complete games (30), and ERA (1.97).

Above: Paperback book, 1973

Below: Sports Illustrated, June 12, 1972

In 1973, the Designated Hitter Rule, in which a player is designated to take the pitcher's place in the batting order throughout the course of a game, was adopted by the American League, which had been starving for offense since before the Year of the Pitcher. Purists were outraged then and still are, arguing that the rule did away with the need for late inning managerial strategy during close games, and that it compromised the integrity of the more-than-century-old game. The DH was initially a boon to aging stars whose fielding skills had slipped a notch or two over the years, but who still possessed acumen at the plate. Later, it opened the door for career DH's: good-hit, poor-field types like Edgar Martinez and David Ortiz. Whatever one's views on the issue, it is an aspect of the game that, unlike the NFL, and despite limited inter-league play, has provided ongoing justification for the existence of two separate leagues, thereby preserving the importance of winning a Pennant in this age of mergers.

Above and below: early DH's, as pictured on Topps baseball cards.

Until Rickey Henderson came along, Lou Brock was the most prolific base stealer in history, holding the Major League records for both single season (118) and career (938) thefts. Over three World Series, Brock compiled a .391 batting average and a record 14 stolen bases. The Hall of Famer is also a member of the 3,000 hit club.

Above: 1973 Topps baseball card

Below: Sports Illustrated, July 22, 1974

Baseball Digest, December 1974

Gaylord Perry, who was the first pitcher to win the Cy Young Award in each league, built his career on the spitball, which has been an illegal pitch since 1920. Or did he just want hitters to think he was loading the ball when he went to his face, hair, hat, and various other parts of his body/uniform between pitches in order to gain a psychological advantage over them? Whichever the case, he was able to win 314 games over a twenty-two-year career in which he drove both umpires and batters to distraction.

1974 Topps baseball card

The great Hank Aaron finished the 1973 season one home run shy of Babe Ruth's all-time mark of 714. The editors of the Baseball Stars series, faced with an off-season quandary, correctly anticipated Hammerin' Hank's eclipsing the mythical record and featured him on the cover of the 1974 edition.

Above: Paperback book, 1974

Below: Sports Illustrated, April 15, 1974

In the early 1970s, America was deep in the throes of a nostalgia craze. The musical Grease, which takes place in the 1950s, opened on Broadway in 1972. Octogenarian Groucho Marx, comedy icon of the early- through mid-20th century, appeared in a one-man live show the same year. In 1973, Peter Bogdanovich's film Paper Moon, set in the 1930s, was a critical and commercial hit, and American Graffiti, George Lucas's paean to his teen years in the early 1960s, made Lucas a bankable Hollywood director overnight. Also in '73, Paul Newman and Robert Redford starred in a wildly popular motion picture about a group of con artists in 1930s Chicago, The Sting. The faux '50s Happy Days became a surprise hit TV show, premiering in January of 1974, and a movie version of F. Scott Fitzgerald's 1925 novel The Great Gatsby, starring Redford and Mia Farrow, made "the Gatsby look" all the rage later that year.

With the fall of his mythic home run record, the Babe was in the forefront of the public's consciousness as well in 1974, in part thanks to one of the first serious biographies of the man. Babe: the Legend Comes to Life, by Robert W. Creamer, is still a must-read. Prior to its publication in book form, selected segments were serialized in Sports Illustrated, beginning with the March 18 issue.

Tommy John was a good, grounder-inducing sinkerball pitcher who had enjoyed some success with the White Sox before coming to the Dodgers (in exchange for Dick Allen) and posting three straight seasons with winning percentages of .688 or higher. He was in the middle of an outstanding year in 1974 when he permanently damaged the ulnar collateral ligament in his throwing arm, something that, unnamed and unknown to earlier generations of pitchers and team physicians, had been referred to simply as a "sore arm" or "dead arm," and usually meant the end of a player's career. But in late 1974 the Dodgers' physician, Dr. Frank Jobe, performed a radical new type of surgery on John's arm, replacing the damaged ligament with a tendon from the pitcher's other arm. After a year John was back on the mound, and within another year he was back to full strength. In fact, he was arguably more effective after the surgery that would be named after him than he had been before, pitching until the age of 46 and winning a total of 288 games.

1975 Topps baseball card

In 1973 Nolan Ryan broke Sandy Koufax's single season strikeout record by racking up 383 K's in 326 innings. He also pitched his first two of a record seven no-hitters in his illustrious Hall of Fame career.

1975 Topps baseball card

Carlton Fisk's 12th inning walk-off home run in Game 6 of the 1975 World Series capped what came to be considered the most dramatic and exciting Game 6 in Series history*. Oh, yes . . . the Reds defeated Fisk's Red Sox in Game 7 to win the Series.

* Until Game 6 of the 1986 Series, that is -- which held the unofficial Most Exciting Game 6 title until Game 6 of the 2011 Series.

Sports Illustrated, October 20, 1975

Above and following: the Cincinnati Reds' 1976 yearbook.

The "Big Red Machine," a moniker the team had earned while winning pennants in 1970 and '72, was firing on all cylinders by the 1975 and '76 seasons, winning back-to-back World Series under future Hall of Fame manager Sparky Anderson. The first was one of the most famous and exciting Series ever (see above), vs. the Boston Red Sox, the second a lopsided laugher vs. George Steinbrenner's and Billy Martin's Yankees. Already boasting MVPs Johnny Bench (1970, '72) and Pete Rose ('73), the Reds had gone from being a very good team to a great team with the acquisition of 2nd baseman Joe Morgan in 1972. Morgan was the MVP in both of the Reds' championship seasons, and would eventually land in the Hall of Fame, along with teammates Bench, Rose, and Tony Perez.

Above: Joe Morgan's 1977 Topps baseball card

Below: Morgan graces the cover of the April 12, 1976 issue of Sports Illustrated

The prospect of sustained success in Boston seemed to be ballooning in the spring of 1976 as the Red Sox's 1975 rookie phenoms Fred Lynn and Jim Rice posed for the April 12th issue of Sports Illustrated. While '75 A.L. Rookie of the Year, MVP, and Gold Glove center fielder Fred Lynn would soon level off into a good, if not spectacular player, left fielder/DH and ROY runner-up Jim Rice would blossom into a franchise player (winning MVP honors in 1978) and Hall of Famer. Their talent pool notwithstanding, the BoSox would not make it to another World Series until 1986 -- which would be yet another ill-fated ordeal for the franchise and its long-suffering fans.

Sparky Anderson, the first manager to win World Series in both leagues.

1973 Topps baseball card

Presumably because of his having played in the same era as catching greats Johnny Bench, Carlton Fisk, and Gary Carter, Ted Simmons was routinely overlooked by Hall of Fame voters for nearly three decades -- despite the fact that his .285 lifetime batting average is sixteen points higher than the best BA of the aforementioned Cooperstown-enshrined backstops (Fisk's). "Simba" was also an eight-time All-Star and held the record for hits by a catcher with 2,472 until surpassed by Ivan Rodriguez in 2007. As for his defensive abilities, his lifetime fielding percentage of .987 is comparable to Fisk's (.988), Bench's (.990), and Carter's (.991). He finally became a Hall enshrinee in 2020.

Ted Simmons signed photo

The expansion Kansas City Royals had risen to the top of their division by 1976, under the leadership of manager Whitey Herzog and the hitting of George Brett and Hal McRae, who finished first and second, respectively, in the A.L. batting race that year. The Royals would win three consecutive division titles from 1976 through '78, losing to the Yankees in all three League Championship Series -- twice in the ninth inning of the fifth and final game. Herzog and Brett would ultimately be elected to the Hall of Fame.

1977 ALCS program

The Minnesota Twins' Rod Carew flirted with .400 throughout the summer of '77. He would finish the season at a lofty .388, matching the highest batting average since Ted Williams' .406 in 1941: the .388 mark Ted achieved in 1957. Carew would end up with seven A.L. batting titles and a .328 career average.

Sports Illustrated, July 18, 1977

Dave Parker, with back-to-back batting titles in 1977 and '78 and a 1978 MVP award, helped keep the Pirates in contention in the N.L. East throughout the latter part of the '70s.

Baseball Digest, July 1977

When Jim Palmer wasn't modeling for underwear ads he was winning A.L. Cy Young Awards and chalking up 20-victory seasons. He was awarded three Cy's in four years from 1973-76 and won 20 or more games eight times for the Baltimore Orioles.

1978 Topps baseball card

Tommy Lasorda in a characteristic pose.

Embracing the Hollywood culture, the flamboyant and vociferous Lasorda was the polar opposite of quiet, dignified Walter Alston, whom he succeeded as Dodger helmsman in 1977. He would lead the team to two consecutive World Series defeats at the hands of the Yankees in 1977-78 before finally besting them in the Series that capped the farcical, strike-shortened split season of 1981.

Sports Illustrated, March 14, 1977

In 1976 Yankee Stadium reopened after three years of renovation, which transformed completely the look and aura of the 53-year-old "House That Ruth Built." The Pandora's Box of free agency had been opened the same year by pitchers Andy Messersmith and Dave McNally.

Baseball would never be the same again.

Above and below: Time magazine, April 26, 1976

Fiery Billy Martin -- who spent a good portion of his managerial career being fired and rehired by Yankees owner George Steinbrenner -- learned his trade while playing for the Yanks in the early '50s, under the tutelage of "The Old Perfessor," Casey Stengel.

1978 Topps baseball card

Never demure, often self-aggrandizing, Reggie Jackson uttered the following words in 1976: "If I played in New York, they'd name a candy bar after me." He signed with the Yankees prior to the 1977 season, and in April of 1978 his prediction came true.

Candy bar wrapper, 1978

Above and following: the 1978 New York Yankees yearbook.

After a then-unprecedented eleven year absence from the World Series -- since 1921 their longest stretch without a Pennant had been three years -- the Yankees were back in the fray from 1976-78, regaining their status as the team everybody loved to hate. It was déjà vu all over again (as then-coach Yogi Berra might have said), only this time it seemed the Yankees hated each other as well: 1977 acquisition and self-proclaimed "straw that stirs the drink" Reggie Jackson didn't get along with 1976 MVP and team captain Thurman Munson or volatile manager Billy Martin, who didn't get along with meddling owner George Steinbrenner, who didn't get along with anybody. By the summer of 1978 all this melodrama collectively had a nickname: The Bronx Zoo. Despite all the backbiting, the team managed to win back-to-back World Series in '77-78. Pitching standouts included 1977 Cy Young Award winner Sparky Lyle (13-5, 26 saves), 1978 winner Ron Guidry (25-3, 9 shutouts), and Rich "Goose" Gossage (league-leading 27 saves in '78).

Hall of Famer Mike Schmidt, considered by many to be the best third baseman of all time, helped usher the Phillies back into the postseason in the late '70s. Schmidt led the N.L. in home runs from 1974-76, and would ultimately set the league record for most HR titles with eight. He collected ten Glove Gloves along the way as well.

Baseball Digest, October 1979

In 1978, Pete Rose, a.k.a. "Charlie Hustle," tied Wee Willie Keeler's National League record by hitting in 44 consecutive games -- twelve shy of Joe DiMaggio's Major League record. He also collected his 3,000th career hit that year, en route to a record 4,256.

Pete Rose signed photo

In 1979 the Cardinals' All-Star first baseman Keith Hernandez came out of nowhere to lead the N.L. in runs scored (116), doubles (48), and batting average (.344), tying him for MVP honors with Pirates first baseman Willie Stargell. Playing in only 126 games, Stargell didn't lead the league in any category, but likely earned props from the writers for being the heart and soul of the "We Are Family" Pirates, who went on to win the World Series over the Orioles for the second time in less than a decade. Hernandez, who also won a Gold Glove in '79, would win ten more of the fielding awards, plus two World Series rings in the '80s.

The Sports Illustrated cover shown below, featuring the editors' choices for Sportsmen of the Year -- N.L. Co-MVP Willie Stargell and Pittsburgh Steelers quarterback and 1978 NFL MVP Terry Bradshaw -- essentially depicts a symbolic changing of the guard, from baseball to football, of the favorite professional sport of the American public. This was particularly true in Pittsburgh, with the Pirates winning their last World Series to date that year, while the Steelers were en route to winning their fourth of six Super Bowls -- even though Roger Angell had written in The New Yorker as early as 1971 of the NFL's popularity surpassing that of Major League Baseball, specifically in the home cities of that year's Series combatants, the Orioles and Pirates.

Above: Sports Illustrated, April 7, 1980

Below: Sports Illustrated, December 24, 1979

“No, that’s what you can never do in baseball. You can’t sit on a lead and run a few plays into the line and just kill the clock. You’ve got to throw the ball over the goddam plate and give the other man a chance. That’s why baseball is the greatest game of them all."

- Earl Weaver, after the Orioles lost to the Mets in the 1969 World Series

- Earl Weaver, after the Orioles lost to the Mets in the 1969 World Series

All items are from the collection of Jon Oye.

This page is not affiliated with Major League Baseball. All original photos or copyrighted material remain the property of their respective copyright owners.

This page is not meant to represent a comprehensive history of Major League Baseball during the 1960s through the 1970s by any stretch. It's basically just a showcase for a portion of my baseball memorabilia collection, which I have taken the liberty of augmenting with a few facts, figures, and comments that fans and lay people alike will hopefully find somewhat informative and/or interesting as they browse through the pictures.

No comments:

New comments are not allowed.